I strongly suggest you read the first half of this article first, because it would be hard to grasp some of the concepts discussed below without the proper context given by me in the introduction.

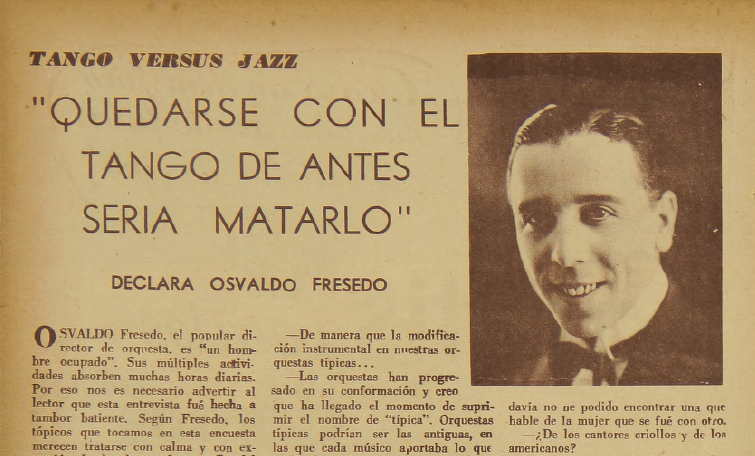

So, now that we got most of the background information out of the way, we can actually start to read and analyze this remarkable interview with Fresedo together. If you understand Spanish and want to read the interview by yourself, go ahead and check out the photo below, but in any case, I am going to actually broadly discuss and contextualize several points raised in the interview, so I still recommend to read my analysis anyway.

For starters, the first thing I’d like to mention is not the main point of my study, but it has to be said: one of the striking aspects of Fresedo’s words below is that he mentions a few things that are common ideas about tango dancing nowadays, but actually already expressed by someone almost 90 years ago, during totally different times. Our beloved orchestra director, described as a “very busy man” (anyone surprised here?), is first asked how he would summarize tango music, and he immediately thinks of the music being very national/Argentine in character, elegant and yet mostly focused on the inner experience of the dancers. And the latter is something that is still peculiar to this day: I don’t think there is any other dance that is nearly as introverted as the tango, with (ideally … “shut up, Lucas!”) dancers focusing on things like the embrace and the connection with someone else and using it to share feelings about the music they dance to. This is at least how tango has been danced since the last few decades, and it’s fun to know it was apparently already the same in those vastly different times!

Now, some of you readers and Cronins and Fauses might protest and wonder why I think tango would have been any different back then, but it’s important to realize there has been a lot of development in tango dancing since the actual Golden Age of the music (+- 1935-1945), and I also personally think the tango danced back then, as seen in old movies, looks a bit strange for modern-day viewers like us. My judgment is limited here as I’m not an expert on dance history, but I do know there is a small amount of tango lyrics that refer to the dance, and they aren’t particularly expressive about the dance as an emotional experience… and yet, at the same time they do offer some hints. Let me show you two nice excerpts, first from Así se baila el tango (which, at the same time, is mostly focused on steps and on looks)….

This is how you dance tango:

our breaths melding,

our eyes closing,

to listen better

to the violins

telling the bandoneon

why Malena has never sung again

since that one night.

(Translation by Derrick del Pilar, tweaked by me)

… and from Muchachos, comienza la ronda (same source, tweaked again):

Guys, the ronda is starting

as the tango invites us to form it.*

Who wouldn’t get up to dance,

when you hear the first notes

of such brilliant music?

We can weave our emotions

into this song

as it touches the depths of our soul.

(*”ronda”, a word even non-Spanish speaking tango dancers may understand, to this day still refers to the counter-clockwise way of social dancing that we naturally form in milongas when a new tanda begins.)

Anyway, there are some more examples of this topic, which pretty much deserves an article of its own. Moving on from this mere detail in the interview (and yet, I’ve written so much already! 😱), one of the two main topics in it is the evolution of tango. In the first half of the article, we argued how tango gradually began to mature already before the official start year of the Golden Age (1935), and how it happened in the case of Fresedo’s orchestra. In our actual interview from those times, Fresedo calls this evolution “necessary”, because (the interview title gets repeated) as “having it remain in the past would mean killing it”. He calls it “fundamental, just like in all other musical genres of the world”, because he sees whatever evolution as beneficial.

We shouldn’t take that last bit too literally considering that in a public interview, a musician wouldn’t really openly criticize others directly and I assume Fresedo and his colleagues, friends, rivals, etc also had differences in opinion about the direction tango music was to take. This is a just a note for us to realize that these interviews can sometimes have diplomatic, cryptic and/or evasive language and we shouldn’t think such publications always tell the entire truth or something. However, and interestingly so, mister F. is still very outspoken about why musical evolution was so important and elaborates about the flaws of the old-school way of playing and composing tango: the musicians were still sticking with simple and inadequate musical arrangements, or in other words, they used limited instrumentation and, especially in the early days of tango, those musicians didn’t even have the required knowledge to do so.

Article continues below…

Fresedo makes a case for a more complicated and mature division of tasks within an orchestra: everyone follows their specific part that has been set out by the director and/or the arranger of a piece instead of just improvising whatever. This more standardized way was already a trend at the time (he acknowledges this) and is probably what is referred to as the “evolution” in tango, but at the same time he’s still saying that a lot of the compositions are still too unorganized and orchestras could still definitely greatly improve their instrumentation. Likewise, he expresses the same for the role of the singer in orchestras and the need to formalize this, no matter if it’s a danceable song or a tango canción for listening. I mentioned before how these interviews can often be a bit diplomatic or evasive, but just imagine the courage Fresedo had to make an argument like this and risk offending other musicians in the scene. And as if that weren’t enough already, the interview then becomes even more remarkable by entering into (American) jazz territory.

Our smiling director not only stresses how much he loves the jazz genre, but even applauds it as some sort of shining light for the future of tango music. And he does so actually for the same reasons he argued for more serious instrumentation in tango: according to Fresedo, the jazz scene in the U.S. had already moved from a similar, rudimentary way of making music into an advanced, standardized, intellectual pursuit that was arguably way ahead of the contemporary situation of tango music, which was still very much inside a transition process. Fresedo declares that “music has no borders” and that he enjoyed a lot of genres, so he incorporated several ones in his repertoire, not just tango. In this context, it’s important to realize that several tango orchestras were indeed playing jazz/foxtrots, Spanish-style songs, rancheras (I think this is a style from Uruguay/Argentina that evolved from the European mazurka, and not the Mexican genre), marching songs, rumbas etc, and continued to do so in the Golden Age. Or as Señor Diabetes concludes the interview: “I am not devoted exclusively to tango, I am devoted to music”.

There are a few highlights left in the dialogue, for example Fresedo’s mixed feelings about tango lyrics, not liking some of the traditional ones about tragic stories in Buenos Aires or with a lot of lunfardo (the dialect of the streets), instead preferring more sophisticated ones that fit his melodious orchestra style. That’s not surprising if you know his type of songs a bit and consider that the orchestra still has this somewhat more upper-class connotation even today. His previously described admiration for the American music he deemed more advanced, ties in with this, and he also expresses the same problem with Argentine jazz musicians, who were also apparently far removed from all the progress made abroad. It is also necessary to underline what happened decades later: in 1956, long after the Golden Age, Fresedo performed together with the famous jazz musician Dizzy Gillespie in Buenos Aires, which led to an interesting recording. This visit was not a coincidence, considering that not only Fresedo but also other orchestras and soloist singers went on many tours abroad and became well-known around Latin America, parts of Europe and the United States. This will be described and illustrated in future posts.

To conclude today’s article, there are two points left I need to make. First, and as a side note, I have to repeat a point I made in the beginning of this second chapter: not just the dancing being a kind of introverted experience, a common idea nowadays, was expressed by Fresedo, but he also says Europeans (and Americans) tended to prefer more melodious and romantic tangos, and that’s the second thing that surprises me so much, because I believe this is still true! Ironically enough, I think Fresedo’s own music from the Golden Age is a true staple of tango DJs in Europe, and much less so in Argentina. This is also true for, let’s say, Canaro with Maida. And just another generalization: I think in Buenos Aires they like instrumental tangos quite a bit more than over here in the Old World. But let us also appreciate the many things that are played in common, by good DJs who understand what quality music for dancing is in many different forms that are all necessary in a milonga: fast and slow, rhythmical and less rhythmical, neutral and romantic, melancholic and lighter, and so forth. We all love good music everywhere, and tango has a lot of good music. Let’s also appreciate that, even though Fresedo praises music as having no borders, tango music still has a very strong identity of its own and is unique in the way it is tied to a local urban culture of immigration of the 20th century, the wonderful Buenos Aires that is reflected in so many ways in the music, and even typical things and “landscapes” from the Argentine countryside are included in it. I don’t think any other country has produced such an amazing package of dance, culture, poetry and music.

And that (finally…🙀) brings me to my finishing point. In the interview, Fresedo mostly described the musical evolution that was happening, and “necessary” according to him, as an increased instrumentation. I think this is what definitely happened especially in the Golden Age (in different stages) and it culminated in, for example, the beautiful, lyrical and mature sound of Troilo and Caló. In the entirety of the Golden Age, making arrangements was a very serious business. But I think Fresedo’s desire for technical progress also eventually lead to what I call the ruining of tango as dance music, as musicians wanted to become more and more sophisticated and tango became essentially a listening genre, eventually. Also, I’d argue there are more factors at play in the maturation of tango music in the 1930s and early 1940s, such as a natural desire to improve the music as a whole (not just in a technical sense), increased creativity, better lyrics, a huge momentum going on with a lot of orchestras competing with each other, tango becoming like pop music for huge crowds of dancers… and I could keep on speculating for a long time. But all these topics will return in future posts, as I’m absolutely obsessed with the Golden Age and its rise and fall. Until then, enjoy listening and dancing to all the gems these people have recorded for you!

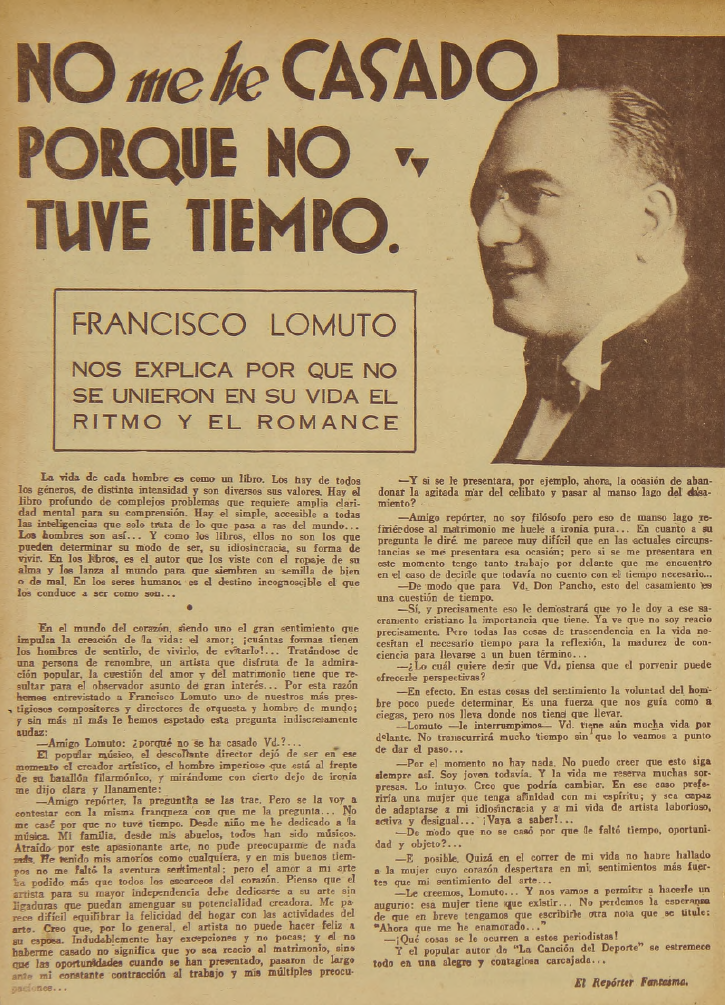

author: not me…

author: not me…